Ménière’s disease is a disorder of the inner ear, affecting your hearing and balance. It can be hard to diagnose because the symptoms can be similar to other disorders, such as vestibular migraine. Testing is essential to confirm your diagnosis and help you manage your symptoms. Currently, there is no cure for Ménière’s disease.

Click the headings below to jump to a specific section.

- What is Ménière’s disease?

- Symptoms of Ménière’s disease

- Causes

- Diagnosis

- Treatment of Ménière’s disease

- Prognosis (outlook for recovery)

- Further information & support

Medically reviewed by A/Prof Rebecca Lim. Last updated September 21, 2023.

What is Ménière’s disease?

Ménière’s disease (MD) is a disorder of the inner ear that causes problems with your hearing and balance. Symptoms include vertigo (dizzy spells), tinnitus (a constant noise in one ear, often described as a buzzing or humming sound), pressure in the ear (aural fullness), and low frequency hearing loss. MD usually only affects one ear.

The incidence of Ménière’s disease is estimated to be about 1-2 people per 1000 (1), although this figure depends upon a number of factors, such as the diagnostic criteria used to define the disease. MD is most commonly diagnosed in people aged between 40-60 years of age, although individuals from 20 onwards may be affected. It is rarely, though occasionally reported in children. Males and females appear to show a similar incidence of Ménière’s.

There is no cure for MD but many people are able to manage their symptoms through medication, lifestyle changes, or in rare cases, surgery.

Symptoms of Ménière’s disease

The typical symptoms of Ménière’s disease occur in episodes or attacks, which involve:

- Vertigo. Vertigo causes dizziness and balance problems. In many cases the spinning sensation can cause nausea or vomiting.

- Hearing loss. Muffled hearing often precedes the attack, and hearing loss may fluctuate throughout the course of the disease. MD also can cause progressive hearing loss which could be permanent.

- Tinnitus. Tinnitus is a ringing or buzzing sound in the ear.

- Sense of fullness in the ear. Many people experience pressure in the affected ear, which is known as aural fullness.

The cochlear symptoms (hearing problems) often precede the balance symptoms such as vertigo. These episodes generally last at least 20 minutes but not more than 24 hours. After a severe attack, most people find that they are extremely exhausted and must sleep for several hours.

In early stages of the disease, the vestibular symptoms (vertigo) or cochlear symptoms may exist in isolation. However, as the disease progresses people usually develop the full combination of symptoms (1).

A handful of patients usually with end-stage Meniere’s Disease also experience ‘drop attacks’, or Tumarkin attacks. This means that they abruptly fall without losing consciousness, and most do not experience ongoing symptoms of dizziness or vertigo at the time of the attack. While the actual attack is brief, it can cause injuries during the fall and be emotionally draining for patients. Many people lose confidence about going out in public. Only around 10% of people with MD get Tumarkin attacks (1).

Causes

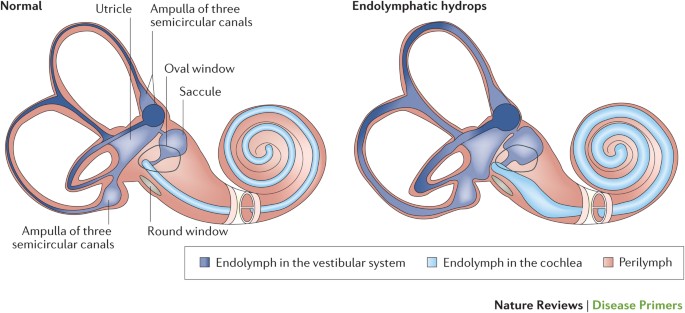

The exact cause of Ménière’s disease is not known. One theory suggests that it could be caused by a build-up of fluid, called endolymph, in the inner ear. This is called endolymphatic hydrops (2).

Normally, the flow of endolymph in the inner ear helps your brain understand how your head and body are positioned. When you move your head, the endolymph flows through the inner ear chambers to activate hair-like sensors in your inner ear. In endolymphatic hydrops, there is too much of this fluid, and it causes disruption of balance and hearing signals.

While endolymphatic hydrops is often found in patients with MD, the exact nature of this relationship is unclear. For many years it was thought to be the cause of MD, but recent studies have found that some people have this fluid build-up without experiencing MD symptoms (2). For now it is considered to be a feature of MD but not necessarily the cause.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will ask you about your symptoms & medical history. The diagnostic criteria for Ménière’s disease involves:

- Two or more vertigo attacks, each lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours, or up to 24 hours.

- Hearing loss proved by a hearing test.

- Tinnitus and / or a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear.

Your doctor might also want to run some tests. Even though there is no specific test to diagnose Ménière’s disease, they often need to rule out other diseases that have similar symptoms. They might refer you to get hearing tests, balance tests, or x-rays.

Treatment of Ménière’s disease

There is no cure for Ménière’s disease. Instead, treatments are available to help reduce your symptoms. There are also certain lifestyle modifications that may help prevent attacks from occurring.

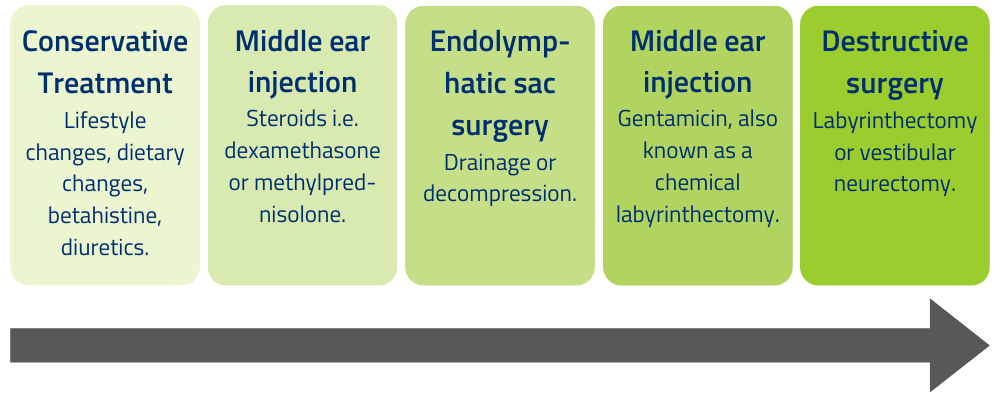

Your doctor will usually start with a conservative approach and progress to other treatments depending on how they work, as outlined in the graphic below (2).

First line treatments

The first and simplest recommendations to treat MD include lifestyle & dietary changes. Adopting a low salt diet is recommended to reduce fluid retention. It can also help to avoid alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco, improve your sleep quality, and decrease stress (2). Many people report that making these changes helps reduce the frequency of their attacks.

First-line medications include:

- Betahistine. This medication affects blood flow to the vestibular system to reduce symptoms of vertigo.

- Diuretics. Diuretics are used because they lower the amount of fluid in your body. This is based on the theory of endolymphatic hydrops.

- Vertigo or anti-nausea medications. During an attack, medications can be used to reduce symptoms of nausea and dizziness. Benzodiazepines and phenothiazines (such as prochlorperazine) are used, but they should only be taken for short periods of time (1).

Some people also find nutritional supplements helpful, although this has not been proven in high quality clinical trials. Ginkgo biloba and ginger could be used as long as you discuss this with your doctor.

Further treatment options

Middle ear injections. Injecting drugs (either gentamicin or steroids) directly into the middle ear can improve vertigo symptoms.

- Steroid injections such as dexamethasone can reduce vertigo symptoms. This usually lasts for a few months and is relatively safe (3).

- Gentamicin is toxic to the vestibular part of your inner ear, so it damages the part of your ear that causes MD symptoms. However, it can also make hearing loss worse.

Surgical options. Endolymphatic sac surgery aims to treat the fluid build-up in the inner ear (endolymphatic hydrops). Labyrinthectomy and vestibular neurectomy are destructive, meaning that they work by removing or impairing the part of your inner ear that causes symptoms. However, they are considered to have the highest possibility of controlling vertigo in patients who don’t respond to other treatments (2).

- Endolymphatic sac surgery aims to normalise fluid levels by shunting, draining, or decompressing the sac. It is a preferred treatment because vestibular function & hearing can be well preserved (2).

- Labyrinthectomy completely destroys hearing and vestibular function in the affected ear. It is often only considered if the person already has significant hearing loss, and if they still have one healthy ear.

- Vestibular neurectomy involves cutting the vestibular nerve so that information about movement and balance doesn’t reach the brain. This usually improves vertigo attacks, and leaves the person’s remaining hearing intact.

Depending on the frequency of your attacks and the progression of the disease, your doctor or a neurologist will be able to advise the best course of treatment for you.

Over time, many patients with Ménière’s disease develop permanent hearing loss in the affected ear. Hearing aids are often used to help people manage this.

Prognosis

There is no cure for Ménière’s disease. MD cannot be treated and made to “go away” as if you never had it. It is a progressive disease which worsens, more slowly in some and more quickly in others. Initially the symptoms and hearing loss resolve completely between attacks, but later there is progressive hearing loss and persistent tinnitus (1).

Many people suffering from MD lead productive, near-normal lives; others face greater challenges in coping. Each individual’s experience will depend on the severity of their symptoms and how they respond to treatments.

After around 5-15 years, many people find that the acute episodes of vertigo will stop. However, they continue to experience a constant sense of mild imbalance, tinnitus, and moderate hearing loss in the affected ear (1). This knowledge can be comforting for people who find the vertigo attacks to be their most distressing symptom.

Further information & support

If you’d like to learn more about Ménière’s disease, recent research, or related resources, you might be interested in the following pages:

- Dr Aaron Camp was the recipient of Brain Foundation grant funding for research into Ménière’s disease in 2019 – read about his grant here.

- Acoustic Neuroma (video) – this was created by A/Prof Rebecca Lim as part of Brain Awareness Week 2023. While it’s not directly about Ménière’s disease, this video includes a helpful explanation of the vestibular system.

- Recent Australian research into Ménière’s disease – PubMed database

Sydney Ménière’s Support Group

The Sydney Ménière’s Support Group was originally created by Anne after she was diagnosed with MD in 2015. Her website now includes a range of articles, webinars, personal stories, and information on support groups across Australia.

sydneymenieressupportgroup.com/

Ménière Society – UK

www.menieres.org.uk

Vestibular Disorders Association – USA

www.vestibular.org

References:

- J Harcourt et al, 2014, Meniere’s disease. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.g6544

- Y Liu et al, 2020, Current status on researches of Meniere’s disease: a review. DOI: 10.1080/00016489.2020.1776385

- JD Sharon et al, 2015, Treatment of Menière’s Disease. DOI: 10.1007/s11940-015-0341-x

DISCLAIMER: The information provided is designed to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between a patient / site visitor and his / her existing health care professionals.

The Brain Foundation is the largest, independent funder of brain and spinal injury research in Australia. We believe research is the pathway to recovery.

The Brain Foundation is the largest, independent funder of brain and spinal injury research in Australia. We believe research is the pathway to recovery.